- Home

- Pauline Black

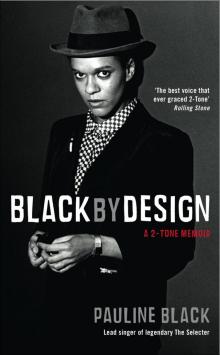

Black by Design Page 12

Black by Design Read online

Page 12

We spent the whole of the month of June rehearsing there or anywhere else around town that would have us if the back room at the Binley Oak was unavailable. Not every day, but probably three times a week. I was still working at the time and had to fit around my night work rotas, which involved working all day, all night and half the next day. Sometimes there would be very few patients that needed X-raying during the night, other times it would be busy all night and the next half-day would feel interminable. It was exhausting, but a good way to make extra money for clothes and records.

There was another bloke who worked in the radiography department, Philip, a very camp young man who had a penchant for Freddie Mercury. He sang in a band too. Its name was Silmarillion (not to be confused with the band that became Marillion). Presumably he was also into Tolkien. Terry and I had been invited to see them gig. I was not particularly impressed, Terry even less so, but Philip could hold a tune rather better than his white boiler suit managed to hold in his portly Pickwickian frame. As regards his black nail-varnished fingernails? Well – let’s not even go there!

Nonetheless he was determined to make it, with all the ferocity of an X-Factor contender. He had the self-assurance of a pantomime dame and regaled me at every opportunity during our working day with how many gigs he had done, what songs he was writing and how best to present himself. Philip’s constant self-obsessed banter could make the time fly by during long stints administering barium enemas to unenthusiastic patients with faulty bowels. Philip and I would do what we had to do while discussing the latest Kate Bush release. An appreciation for the divine Ms Bush was really the only thing we had in common.

I wanted to confide in Philip about the new band that I had joined, but unfortunately he never seemed interested when I explained that the music we were doing was ‘sort of reggae’. He thought reggae was boring and unsophisticated, whereas Kate Bush’s ‘Wuthering Heights’ was pure genius. So I shut up, content to know that it looked as if The Selecter’s first show would be far away from Coventry. Philip hadn’t managed to negotiate such a feat yet.

Strangely enough, a few months later The Selecter’s first hit record ‘On My Radio’ was reviewed on BBC Radio 1’s teatime record review show, Roundtable, by none other than Ms Bush herself, who gave the song a resounding thumbs up, while remarking that my falsetto vocal on the chorus reminded her of ‘Wuthering Heights’. I hope Philip was listening.

By the end of May we had a set list of about ten songs. There was an instrumental opener, a version of the Upsetters’ ‘Soulful I’, which featured Desmond’s considerable abilities on Hammond organ. The sound of his playing, coupled with the energy of his antics behind the keyboard, were guaranteed to get people’s attention. We didn’t know it at the time, but we were on a steep learning curve. Each of us rose to the occasion because subconsciously we knew that this was a way out of the rat race. This was a way to express how we felt about the society we lived in, but above all, it was a new way.

Slowly, we were familiarising ourselves with each other. I began to realize that I was the only person in the band with a bona fide job, although Neol had recently worked at Lucas Aerospace in Coventry. In fact, he had penned the lyrics to ‘Too Much Pressure’ while there, after experiencing ‘the day from hell’. Everybody else was either on the dole or ducked and dived in and around Coventry.

Charley’s place became an ‘open house’. Many Selecterites hung out there of an evening, listening to his old ska, bluebeat and rocksteady records. It was an easy time between us all. I was in my element, eagerly assimilating a new music, genuinely interested in all aspects of ska and reggae culture. I quickly realized that there was a general absence of women involved in the early days of ska music. Much later I discovered that there were quite a lot of women who sang back then, but given the heavily patriarchal Jamaican society, male singers were favoured. Women singers were considered less important and ended up forgotten or as backing singers.

An exception to this rule was Millie Small. Of course I’d heard her sing ‘My Boy Lollipop’, along with most of Britain, back in 1964. This jaunty slice of pop had sold 600,000 copies. Charley was at great pains to point out to me that it was a bluebeat song, not a pop song, and the first Jamaican record to rock the British nation.

Our first show was in Worcester. I can’t remember the name of the venue. Thank goodness things like mobile phones, Twitter and Facebook had not been invented yet, otherwise I am quite sure that our careers would have been stillborn before we had got to the end of the first song.

By this time, we had the music in embryonic form, but unfortunately not the style. I fetched up with an Afro, which was trendy all through the late ’60s and mid-’70s, but in 1979 it was beginning to look rather tired. The immense candy floss creation that graced my head in 1968 for the physics class denouement now looked as though it had shrunk in the wash. It was a more manageable Michael Jackson circa ‘Off the Wall’-sized ball, more associated with the disco crowd than any conscious reggae band. To add to the illusion that I was a backing singer for Chic, I was wearing pink spandex trousers and a tight white T-shirt scattered with pink sequins! Embarrassing to admit but true. My style choice had been made more out of ignorance than any real sense this was the ensemble I desired. The truth was that I didn’t know how I was supposed to dress for this kind of music, so I just copied what I’d seen black women wearing on Top of the Pops.

Charley’s locks were long by this time, so he was cool in that department, but his fawn safari suits were well out of order. Desmond, Aitch, Gaps and Commie still didn’t know in which camp their hair belonged, much less their clothes, an assembly of denim flares, badly patterned sleeveless jumpers, and an assortment of hats, none of which were pork pies or trilbies. Money was the main issue of course. Any extra money was spent on marijuana; there never seemed to be a moment when there was not a spliff on the go or being rolled or stubbed out.

Dope smoking in this extraordinary quantity was new to me. I smoked occasionally, but not every hour of the day in which my eyes remained open. In this world of weed, clothes were a low priority. So was punctuality. I learned patience is indeed a virtue when the clock runs according to a Jamaican man’s understanding of ‘soon come’ time. Charley was never late, because he was clever enough to make us all meet at his house, but Desmond and Aitch could be up to two hours late, which made people very fractious before we’d even fetched up at the gig.

The Worcester gig was in a draughty, rundown, wooden-floored hall with a proscenium arch stage at one end better suited to sermons than live gigs. There was no in-house PA. Our sound was made audible through a mish-mash of different-sized speakers borrowed from a Coventry sound-system and mostly inaudible microphones, operated by an inadequate mixing desk set. A surly-looking hanger-on, the imaginatively named Chris Christie, was enlisted to operate this audio mess. No matter really, because we played to three people, not even a dog in attendance.

Welcome to the world of the haphazard happenings, because that was how our gigs came together. Everybody was late all the time and when they did arrive, they had invariably left something behind at home, so somebody had to drive them back to get it. There was a never-ending list of obstacles to be overcome before the band could even start out on the road, let alone do the show. But with the brass-neck bravery of youth, all the problems got solved and somehow we would end up on stage. That’s when the magic happened. All seven of us together was a magical, alchemical thing to behold, as anybody who was conscious back in 1979 and saw the 2-Tone tour would agree.

Gaps and I had the words taped across the front of the stage, just in case we forgot them. This led to a lot of movement on our respective parts as we followed the words along the front of the stage. Thus developed our style of running and skanking anywhere and everywhere. In those days the hour we spent on stage was probably akin to a three-hour gym workout. Even in Worcester.

The Worcester gig happened on 2 July 1979. The band that turned up to the next g

ig at the F Club in Leeds on 10 July 1979, a scant week later, was almost unrecognisable.

In the intervening week, Neol and Jane had taken it upon their collective selves to sit us down and give us a good talking-to about image, how we presented ourselves to the public. They said that it was not enough to have personal style, we had to fashion a coherent band identity. They suggested that we look at the kind of stuff that the Specials were wearing and adapt it to our own tastes. We were also informed that we needed to do a photo shoot as soon as possible. These guys meant business, I thought.

Jane took me on a shopping expedition. She favoured second-hand shops. This caused a problem with some of the guys in the band because Caribbean people don’t like wearing other people’s cast-offs. They want to buy new clothes with their money, not clothes that other people don’t want any more, or worse, ‘dead man’s threads’. That’s why hip-hop artists dress themselves in designer stuff and bling. Black people don’t want to look poor, as though they haven’t got the money for store-bought clothes. Plus, Charley, Commie, Aitch, Gaps and Desmond favoured the African heritage-type stuff that Bob Marley and the conscious reggae artists wore, which to my mind looked equally cool.

It didn’t bother me very much. I didn’t shop at secondhand places, but I knew plenty of white girls who did and they always looked sharp and distinctive, mainly because they weren’t wearing the latest deliveries to Top Shop or Miss Selfridge. It wasn’t something I was much interested in, but I did like to look fashionable. Hence the pink spandex trousers, which were mightily in vogue at that time in the ladies shops I’ve just mentioned.

Under Jane’s tutelage I started to frequent the second-hand shops that used to be opposite the Arts faculty at Lanchester Poly. Jane had a good eye for stuff and I was happy to follow her direction. We took the ‘rude boy’ look that Peter Tosh had pioneered in his early ska days and feminized it. It was just a question of changing the proportions of the garments. She picked out some beige Sta-Prest for me, which were probably from the previous ska era, circa late ’60s. They stopped an inch shy of my shoes, which I was told was ‘cool’. An orange, slim-fit, boy’s Ben Sherman shirt was poked through the changing room’s curtains to cover the upper half of my body. Next she handed me a double-breasted jacket made of shiny grey material. It fitted perfectly. Job done. We sourced a pair of black penny loafers at a downmarket shoe shop, Ravel. White socks took up the spatial slack between the trouser bottoms and my shoes. We decided that my Afro hair did not suit this new ensemble, so I pulled it up into a small topknot. I felt curiously empowered when I tried the clothes on at home and surveyed the result in the bedroom mirror. The addition of a pair of fake Raybans, strictly for posing purposes, finished everything off very nicely.

‘Is that what you’re going to wear on stage?’ Terry asked as he passed our bedroom door and caught the first glimpse of the new image.

‘Think so,’ I said. ‘What do you think?’

‘Different.’

Not exactly a thumbs up, I thought, but I instinctively felt that I was on to something and I wasn’t going to let anybody’s lack of enthusiasm get in the way.

The photo shoot came next. The photographer was a local young man, John Coles, who hauled us off down under the flyover which crosses the Pool Meadow roundabout. It was a spooky twilight shoot and all the more effective for it. When it got too dark we ended up at Charley’s house yet again, posing for photos in the kitchen. I think I like these photos the best out of all the other more obviously expensive shoots we did later. The photos capture the joy of a band at the beginning of its life, assured that success is its for the taking, all it has to do is keep playing and following the yellow-brick road.

By this time Charley and Neol had made contact with John Mostyn, a band manager in Birmingham, who ran the Oak Agency. Hitherto his main claim to fame was as Brent Ford of the imaginatively named band, Brent Ford and the Nylons. I’m told that he used to go on stage with the leg of a pair of tights on his head. Whatever turns you on I suppose.

John Mostyn was already booking shows for the Specials, picking up on the buzz surrounding the ‘Gangsters v. the Selecter’ single, so when John realized Neol’s instrumental had metamorphosed into an actual band, he was more than happy to book us too. This is why many of our early gigs were as support to the Specials. The first of these shows was at the F Club in Leeds.

When the band gathered outside Charley’s house, ready for the gig in Leeds on 10 July, all of us looked much more polished. People had suit bags holding modish get-ups. We also had a couple of roadies, Grant Smaldon and Rob Forrest, two young Coventry lads who spent much of their time signing on and hot-knifing dope at Gaps’s flat in Pioneer House, Hillfields. Rob, who dearly loved the band, had acquired an old, badly re-sprayed, battered and rusty green Bedford van, which he offered us as transport. We were now a fully functioning band. Next stop Leeds.

The F Club (the F stood for Fan and it was sometimes known as the F Club at Brannigans) was a moveable feast in those days. It was smallish, with a capacity of about 250 to 300. We were supporting the Specials – our ‘big break’ as Horace refers to it in his autobiography, Ska’d for Life. Gee, thanks Horace. Much obliged to you, sir, for pointing that out (touching one’s forelock is optional)! ‘Gangsters’ was riding high in the charts and the Specials were capitalising on its success and also on their notoriety from the tour that they had done with the Clash the year before.

On arrival we were informed that there would be no soundcheck for us, because the Specials’ soundcheck had gone on too long and now everybody had gone to the pub next door. So, while the band set up their gear in front of the Specials’ noticeably more expensive equipment, I familiarised myself with the layout of the dressing room. There were no separate facilities for the lady of the band except the toilet – a fact that you get used to fairly early on if you are the only female in a band. Plus anybody can come striding into the dressing room any time they want, which is not so good when you are only half dressed. Failing to knock on this particular day was the unholy duo, Rex and Trevor, the renowned original Specials ‘rude boy’ roadies. They politely introduced themselves: ‘Wh’appen, sis.’

By now, I had learnt that this greeting was a friendly and usually benign exchange between black males and females, even if you weren’t bona fide siblings. So I said: ‘Hello.’

The subtext of the glance exchanged between them was definitely: ‘Shit, we’ve got a right one here.’

‘You singer, right?’ enquired Rex.

Without waiting for an answer, I noticed them check out my new ensemble of Sta-Prest, shiny grey jacket and loafers. I must have passed muster because Trevor immediately suggested, with a particularly cheeky, yet endearing grin, that the thing I most needed at that moment was (no not that!)…a hat.

He escorted me to the Specials’ dressing room with Rex chortling along behind. We were alone in the room, because the Specials were preparing for the show in the pub. I noticed that their dressing room was a proper room containing comfy armchairs, a three-seater sofa, heavily stained, but a sofa nonetheless, and a fridge with assorted beers and soft drinks, and a plate of sandwiches and bowl of fruit on the rickety table. Our dressing room was part of the cloakroom: rows of hard, bench-like seating with hooks to hang clothing. It reminded me of the changing rooms in my school’s gym. Knowing where you were in the pecking order of the bands did not confine itself to the position on the bill. The worth of a band is in the detail.

A dense cloud of acrid ganja smoke hung in the stale-smelling room.

‘You want something from the rider?’ Trevor asked as he saw me eyeing up all the goodies. He handed me a bottle of lager.

So this is a ‘rider’. I’d heard Neol and Charley use the word when talking about gig fees and whether they should ask for a rider. Obviously they hadn’t asked for one from this promoter.

‘Yeah, thanks,’ I stammered out. Trevor handed the bottle to Rex, who removed the cap with his teeth. Q

uite a party trick, I thought. I took the proffered bottle. Then I was shown an array of hats. I tried on a few, but they all looked a bit too butch for my purposes, until I alighted on a dove-grey fedora with a dark grey ribbon hatband. As soon as I tried it on, I felt perfectly attired.

Finding the right hat for oneself is a fraught business. Hats can make some people look totally ridiculous, either because their facial physiognomy doesn’t fit the hat or because their ears stick out or something. Some men look like Freddy ‘Parrot-Face’ Davies in a hat, others look like Humphrey Bogart. I wanted that Humphrey look; that cool, ‘if I snap my brim at you then you’ll do anything for me’ look. That’s what the grey fedora gave me. It was perfect. I looked at Trevor with that look of ‘Please let me have it, I’ll pay you’, but to no avail. He said that I could borrow it for the gig. Thus the image was born, it just hadn’t been named yet.

It was at this point that we collectively found out what it meant to be the ‘support act’. The sound and lighting crew returned from the pub about half an hour before we went on. Lengthy negotiations ensued. It would cost us £10 if we wanted the sound guy to operate the mixing desk and PA. Basically this meant that he made sure the instruments and vocals were audible to the audience, but without any ‘fairy dust’ additives, such as reverb on the vocal mics or echo effects on some of the instruments. These ‘extras’ were reserved for the main band, so that they sounded better than the support. Unbeknown to me in those days, the sound guy would also turn the PA to half volume for the support band, so that when the main band came on they would sound louder, which obviously sent a surge of adrenalin and anticipation through the audience. So many tricks of the trade had to be learned. The lighting guy also wanted a tenner to switch on the lights while we performed a half-hour set. They both knew we would pay up, because there’s no point performing if the sound is inaudible and the band can’t be seen. We were only being paid £50 in total, so there wasn’t much left after the agency took their cut, to pay for petrol and the roadies. But we didn’t mind. We had an audience to impress.

Black by Design

Black by Design