- Home

- Pauline Black

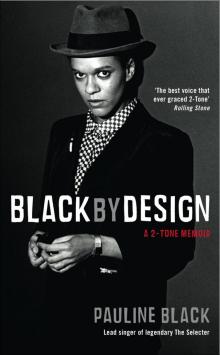

Black by Design

Black by Design Read online

Born in Romford, PAULINE BLACK is a singer and actress who gained fame as the lead singer of The Selecter. After the band split in 1982, Black developed an acting career in television and theatre. She won the 1991 Time Out Award for Best Actress for her portrayal of Billie Holiday in the play All or Nothing at All. The Selecter reformed in late 2010 and have recorded a new album Made In Britain due for release in autumn 2011.

BLACK BY DESIGN

A 2-TONE MEMOIR

PAULINE BLACK

A complete catalogue record for this book can

be obtained from the British Library on request

The right of Pauline Black to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

Copyright © 2011 Pauline Black

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher.

First published in 2011 by Serpent’s Tail,

an imprint of Profile Books Ltd

3A Exmouth House

Pine Street

London EC1R 0JH

website: www.serpentstail.com

ISBN 978 1 84668 790 7

eISBN 978 1 84765 762 6

Designed and typeset by Crow Books

Printed and bound in Great Britain by Clays, Bungay, Suffolk

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Grateful acknowledgement: Quote on pp 387–8 is from The Velveteen Rabbit by Margery Williams. First published in Great Britain in 1922. Published by Egmont UK Ltd London and used with permission.

For Jane (1950–2008)

CONTENTS

Acknowledgements

PART ONE

WHITE TO BLACK

1 A white lie

2 ‘I’ll have some of that’

3 ‘What a wonderful world’

4 A lost glove

5 ‘Do you wanna be in my gang?’

PART TWO

BLACK & WHITE

6 White heat

7 ‘A bird’s eye view’

8 Too much pressure

9 Wake up, niggers!

10 Selling out your future

PART THREE

BACK TO BLACK

11 Deepwater

12 Dark matter

13 What do you have to do?

14 Mission impossible

15 The Magnus effect

16 How do you solve a problem like Belinda?

17 Crash landing

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Everything I have to say about my particular life’s journey is written in these pages. It is too late to qualify or worry unduly about what I have said. Suffice to say that I believe it to be the truth.

Much of this book is based on personal diaries, memories or oral family histories. I have tried to give a truthful approximation of what was said to me or relayed by a third party. For the sake of privacy, some of the characters that appear are composites of people I have known and in a few instances names have been changed.

My thanks to author Tony McMahon for initially introducing me to his literary agent, Oli Munson, who generously signed me to Blake Friedmann and suggested that I should consider writing my memoir. Oli singularly nursed this project through, from tentative beginnings to finished draft manuscript with careful readings, kind consideration and thoughtful observation during those periods when occasionally my inkwell ran dry. I also thank him for introducing me to Serpent’s Tail publisher Pete Ayrton and my dedicated editor, John Williams, who both showed enthusiastic support while shepherding Black By Design to a final manuscript. Thanks also to everybody else at Serpent’s Tail, particularly Rebecca Gray and Ruth Petrie for firm attention to detail and Anna-Marie Fitzgerald for her unstinting organization.

Thanks to Nella Marin and Linda and Pick Withers, who provided safe London havens during my theatrical years and those friends who supported, encouraged and listened to me during the writing process, especially Esme Duijzer and Paven Kirk, who generously read my scribblings at an early stage and provided useful feedback. Thanks also to members of The Selecter, both past and present, who have provided me with a surrogate, if sometimes unruly, family for over thirty years.

My fond gratitude goes out to the Vickers family, Murphy family, Adenle family and Hamilton family, without whom my tale would never have been told. Four families spread across three continents to tell one story. I love and respect them all.

Lastly, my heartfelt thanks to my wonderful husband, Terry, who supported, listened and encouraged me when I wailed, railed and cursed while bringing my story to the page, and who helpfully provided the solution to many a lapse of memory on my part. I love you dearly.

PART ONE

WHITE TO BLACK

ONE

A WHITE LIE

1958, aged 4

My earliest memory is of vomiting the breakfast contents of my stomach onto a pile of starched white sheets that my mother had just finished ironing. I succeeded in Jackson Pollocking all of them. She was not amused, but then again it was her own fault: she shouldn’t have told me that I had been adopted.

It was the late summer of 1958 in Romford, a newly expanding market town in the county of Essex, famous for the stink of its Star brewery, ‘a night down the dogs’ at the local greyhound racing stadium and as the one-time residence of the infamous Colonel Blood, the only man to have stolen the Crown Jewels, even if only temporarily. This backwater suburb was only fifteen miles north-east of London’s buzzing post-war metropolis, but a light year behind in terms of progressive thinking.

My mother was astute enough to know that, since I was about to start infant school, I should be told the truth about my origins, just in case my new pale-faced schoolmates asked me why I was brown when my parents were white. I had noticed that I was different, but I hadn’t realized that it was any kind of a problem. Well, nothing much is a problem at four years old, other than not getting what you really want for birthdays and Christmases.

‘Why didn’t you tell me you felt sick,’ screamed my mother, as she landed a huge smack on my right leg, grabbed me by the arm and sent me upstairs to my bedroom as punishment. ‘As if I haven’t got enough work to do,’ she shouted as I howled my way upstairs.

I sat on my bed, running my hand over the large red handprint on my calf. The mark on my skin felt hot and tender, but the indelible print her words had left on my being was cold and hard.

In her defence, I have to tell you that she was taking Purple Hearts at the time, aka Drinamyl, a potent combination of amphetamine and barbiturate, a form of prescription ‘speed’ that was doled out by GPs from 1957 onward for menopausal women. It was also the drug de jour of the soon to come swinging ’60s, loved by the Mods and Rockers that my mother’s generation would so vehemently hate.

Since her marriage to Arthur Vickers at eighteen, she had spent nearly two and a half decades bringing up four sons, Trevor, Tony, Ken and Roger. She was now a ‘woman of a certain age’ who tired easily, but was still expected to fulfil a monotonous list of housewifely duties without the abundance of today’s labour-saving devices. So drug companies made it their business to invent various potent little pills to help such women get the jobs done quicker. How else could women achieve the ‘perfect fifties family home’ that Hollywood films popularized and spouses expected? Unfortunately these little ‘pick-me-ups’ made her hopping mad about the least little thing.

I jumped off my bed and stared at my tear-stained face in the dressing table’s triptych mirror. I looked different. Then I understood why. I was now a little ‘coloured’ girl who didn’t have a real mummy and daddy. This new

piece of information didn’t fit me. It was like trying to insert the last piece into a jigsaw, only to find that it belonged to another picture.

My brain buzzed with all the new words that my mother had used. She had said that my ‘real’ father was from a place called Nigeria. Apparently he had dark-coloured skin. My ‘real’ mother had been a schoolgirl from the nearby town of Dagenham. No mention was made of the colour of her skin, so I assumed that she wasn’t ‘dark coloured’. This ‘darkness of colour’ was said in such a way that I instinctively knew that it wasn’t seen as a good thing.

Until then, the only thing that had marred my blissfully ignorant existence was my hair, which was alternately described as ‘woolly’, ‘wiry’ or ‘fizzy’ by three curious old aunts, all named after various fragrant flowers. Their cold, arthritically knobbed fingers, like the gnarly old winter branches on bare trees, loved to grab handfuls of it when they visited.

My least favourite aunt, named after the thorniest flower, usually dripped disappointment like a leaky tap whenever she talked about me. ‘Ooh-er,’ she invariably said as she rubbed a section of my hair between her forefinger and thumb, testing its texture, ‘I thought it was going to feel like a Brillo pad, but it’s soft, just like wool.’

Just to put her into context – she had sent me a golliwog for my first birthday present, which, ironically, I cherished for much of my childhood.

Another aunt, whose name evoked a tiny purple flower with a golden centre, was kinder and helpfully suggested to my mother: ‘I heard that you can tame all that fizz with a wet brush.’ She always used the word ‘fizz’ instead of ‘frizz’, as if I was an unruly bottle of pop that had been shaken too much.

My third aunt, who was named after a fragrant flower that grew in valleys, was the only one of this sisterly triumvirate who thought my hair was pretty, but she was half blind. Her cloudy eyes had the same distant, yet myopic look that all cataract sufferers share. ‘Just like candy floss,’ she would say, as she patted my hairy confection.

Now it seemed that not only my hair was a problem, but the colour of my skin too. My mother had told me that I was a ‘half-caste’, a polite term back then; politically correct phrases like mixed race, dual heritage, people of colour, Afro-Caribbean, Anglo-African were as yet unknown in those halcyon days of fifties post-war Britain. The ownership of colonial overseas dominions allowed British citizens to exercise their God-given right in calling a spade a spade. You could even get away with saying ‘wog’, ‘nigger’ or ‘coon’, especially if you wanted to practise a ‘colour bar’ in your local pub or club. Those ‘darkeys’ had to be kept out at all costs.

As I grew, I began to understand that these derogatory terms were standard in our family when describing a black person. Slowly and surely, I realized how un-level the green and pleasant playing fields of England really were, but I was a resourceful child and quickly learned to ignore the colourful jibes hurled by complete strangers on the street when I was unaccompanied. I always considered ‘jungle-bunny’ the funniest insult I ever heard. I used to wonder how the users of this phrase could be so misinformed. Didn’t they watch Desmond Morris’s Zoo Time programme on children’s television? Rabbits didn’t live in the jungle; they preferred more temperate climes. I soon understood that ‘getting it all muddled up or just plain wrong’ is the main stock in trade for any good racist worth their salt.

Black people were still a rarity on the streets of Romford. Nobody ran up and touched you for luck any more – as my mother explained that she and her school friends did the first time that they saw a black man – but being the only black kid in school did make me an automatic target for some of the more uncharitable children who made monkey noises in the playground or school corridors. When I mentioned it to my mother, she would say things like: ‘Just tell them that sticks and stones may break my bones, but names will never hurt me.’

It was her attempt at elastoplasting the hurt but, believe me, that jingle is hardly an incisive retort when going head to head with the local primary school bully. A playground thug rarely wants an in-depth discussion about the pros and cons of trans-racial adoption in modern society. The laser-like precision with which such kids seek out the soft underbelly of their object of derision, before putting the metaphorical boot in, must stand them in good stead for future careers as managers or stand-up comics. Almost instinctively I empathized with the ugly or fat school kids who suffered the same kinds of verbal abuse. Being marginalized at such a young age makes children defensive and prone to moodiness. I was good at both.

‘Don’t sulk,’ my mother would bark at me. ‘What have you got to be miserable about? You should think yourself lucky that you’ve got a good home. Lots of little girls like you haven’t, you know.’

What she really meant was that I should consider myself lucky that I had been adopted. It never occurred to her that having your history erased and replaced with somebody else’s version of it was a dubious kind of luck. Adoption is like having a total blood transfusion; it may save your life in the short term, but if it’s not a perfect match, rejection issues may appear much later.

In the tiny microcosm that I inhabited as a child, the word racism hadn’t yet been invented. The concept was alive and kicking, but in the absence of a name it thrived like an inoperable cancer. Ignorance breeds ignorance, particularly when newspapers run inflammatory headlines about being ‘overrun’ or ‘swamped’ with people of a different race. It wasn’t just black people, the Irish got it in the neck too, and the Poles and the Italians, but blacks were highly visible on British streets, therefore they took the brunt of the opprobrium. I frequently heard stupid comments from family members or friends about their brushes with members of the black community.

My mother’s nephew, Alan, was a gas meter reader in Stoke Newington. His job allowed him into people’s homes, so he got to see things that were hidden from the general population. He was always welcomed with open arms whenever he turned up at family gatherings such as funerals, weddings and christenings, because his lurid tales livened up even the most sombre occasions. He brought news from far-off frontiers, the kinds of places that white people ordinarily feared to tread. He confirmed their worst fears.

After liberal quantities of beer he would grow red in the face and begin to wax lyrically: ‘You should see the way some of them darkeys live. Twenty to a room. Take the doors off the hinges and sleep on them, some of them. Have to pick my way across the floor to the cupboard just so’s I can read the meter. ’S wonder I don’t fall over sometimes.’ Such insights aroused audible intakes of breath from the adults.

‘And the smell of their cooking. What do you think of this then?’ he would say conspiratorially, comically looking over each shoulder for effect. ‘I saw loads of open tins of cat food on the kitchen table. Not a cat in sight.’

When his audience looked at each other uncertainly, as if they didn’t quite understand what he was driving at, he would land the punch line. ‘That’s what they eat.’

‘Oh,’ the audience would collectively murmur, finally satisfied.

The stories were always the same. Nobody seemed to notice the repetition or the little black girl listening in alongside.

All Our Yesterdays, a bleak documentary television series about the Second World War, was also on permanent repeat throughout my childhood, just like Alan’s stories. Once I’d seen Alan in his gas meter man’s uniform, his blond hair sticking out of the back of his peaked cap, his moustache small, oblong and freshly trimmed. He reminded me very much of the peaked-cap, rain-coated men who stood by watching as filthy, skinny people in stripy pyjamas were herded into squalid rooms full of bunk beds. The dour commentary explained that these uniformed men were Nazis rounding up the Jews. When pictures of lifeless bodies being bulldozed into freshly dug pits appeared on the screen, my mother would leap up from her armchair and switch the television off. ‘Enough of all that. We don’t need to see all that again.’

But I did want to see it all ag

ain. I was fascinated. I’d never seen real dead people before, particularly not being so unceremoniously buried. Their arms and legs flopped around like rag dolls. From what I could understand at the time, being Jewish was similar to being ‘coloured’. Nobody much liked you if you were either. Even then I realized that being ‘different’ could lead to bad things happening.

After one of Alan’s sessions at a distant relative’s wedding, I asked my mother why these ‘dark people’ – my mother’s terminology (she didn’t seem to be able to say ‘darkeys’) – had to sleep so many in a room. Without missing a beat she replied: ‘That’s the way they live. They’re not like us.’

I wasn’t sure whether she included me in that ‘us’. Indeed, sometimes I couldn’t quite figure out where I fitted into this inequitable equation. I implicitly understood that most of the white people I knew thought that most black people were not as clever as them. I think it was this erroneous assertion that first ignited my somewhat competitive nature when I was a child. I considered it my duty to prove them wrong by making myself as clever as possible. This did not make me popular with my youngest brother Roger, a prototypical ‘Dennis The Menace’, who became, probably understandably, jealous of my early achievements.

I was dispatched to piano lessons when I was five, because my Aunt Violet thought I might be musical. ‘They’re always singing and dancing when you see them on the telly,’ she said knowledgeably.

Roger and me in Clacton, 1957

‘Why don’t I get sent to piano lessons?’ Roger asked whenever he heard me practising on the newly purchased upright piano. Nobody had the heart to tell him that he could barely read and write coherently at the same age as I was taking my Grade 2 piano exam. It wasn’t that he had any yearning to play the piano. He hadn’t even thought about piano lessons until then. He just couldn’t bear the fact that I played well after only a few sessions. Surely he was cleverer than this little black girl who had usurped his coveted position of ‘youngest’ in the family? As soon as he left secondary school at fifteen, he became a Teddy Boy. In his late teens, a local beehived girl hurried this drape-suited, pencil-moustachioed rebel without a clue up the aisle. She later produced a niece and nephew for me. When the children were old enough to talk, they frequently referred to me as ‘chocolate aunty’ – out of the mouths of babes.

Black by Design

Black by Design