- Home

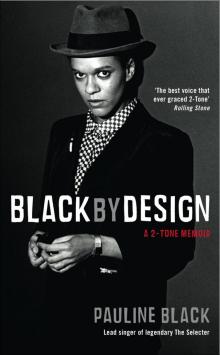

- Pauline Black

Black by Design Page 21

Black by Design Read online

Page 21

Chrysalis hurried to put out the album, hoping that when the single was seen in context with the overall sentiments of the album, it would be looked at anew and interest would be stimulated again. This was a sound hypothesis, but even this salvage attempt was blown out of the water when John Hinckley Jr decided to try and waste the President of the United States, Ronald Reagan, on 30 March 1981. No further mention of the album was made on Radio 1. Thus sounded the death knell of The Selecter.

I think ‘Celebrate the Bullet’ is a forgotten classic of 2-Tone, on a par with ‘Ghost Town’ in terms of orchestration and arrangement, but with a more oblique message. It was an own goal for Neol Davies. Without a hit single, both the British tour and sales of the album were in jeopardy. Neol had told us all to prepare for success. Now we silently stared into the abyss while arguably making the best album of our careers. I stand by ‘Celebrate the Bullet’ wholeheartedly. It is a proud album of a proud band. We were rowing against the tide and ultimately were swamped in the mighty swell of the ’80s pop market. There was no place for us in the musical world any more. People were becoming bored with music that contained some social message that they only half understood, or couldn’t care less about. The only problem was that deep down, none of us had realised it yet.

Also we had embarked on a new way of styling ourselves. Neol’s wife Jane had designed the album cover of Celebrate the Bullet. Her logo for the band, which looks like a red, white and black ‘pie chart’ and is affectionately known as the ‘piece of cheese’ in some circles, is also her design. She was a disaffected art student who had wanted to go to St Martin’s but unfortunately, for whatever reason, didn’t get in. Neol once said in an interview that this was because she was from a working-class background and thus she was ruled out for entry. This may or may not be true, but suffice to say she had not had the kind of training that allowed Jerry Dammers to create the idea for our Too Much Pressure album artwork. She was perhaps not the best person to start styling a band or producing professional artwork at a time when the band’s career was in serious jeopardy and could have benefited from a designer with real vision.

Her band styling was absurd. It was decided that I should rid myself of my hat and let my hair show. Essentially, it was considered a good idea to feminise myself so that we would appeal to a wider cross-section of people. In retrospect this was a terrible mistake and I should have had the foresight and sense to resist, but at times I am the kind of person who says ‘anything for a quiet life’ and, to be perfectly honest, I was by now totally at sea. Neol grew pointed sideburns and looked as though he was Daryl Hall’s clone and Gaps looked like a maracas-playing escapee from a soca band. I could go on, but I’ll stop there.

I’ve never been big on diplomacy. The entertainment industry, as I see it, doesn’t understand the meaning of the word either. When a band has outstayed its welcome and is deemed to have wasted too much money at a record company, then it is out on its ear and that’s that. I could see such a life-threatening storm coming. I’d had enough. I jumped ship and promptly found myself floundering in deep water.

PART THREE

BACK TO BLACK

ELEVEN

DEEPWATER

After leaving The Selecter, I suffered from a recurring dream almost every week for a couple of years. Each night, somewhere in my dream cycle, I lay submerged on the cool tiles at the bottom of a swimming pool. The surrounding water was a deep blue colour. As I looked up there were people sitting along the pool’s concrete edge, all crammed up against each other, furiously kicking their legs, their dangling feet looking like frayed bits of grey felt as they thrashed in the water far above. Their shimmering faces were contorted with laughter. They were oblivious to my plight. I had drowned, but I could still see. ‘Danger 15ft deep’ was ominously written in huge black letters halfway down the wall at the pool’s deep end. The words gently swayed in and out of focus with the ripple effect of the water, just like my last few conscious moments. It always said 15ft.

It was easy to attach significance to the dream. The abrupt departure from the band had been overwhelming. Just as I had been unprepared for such quick success, I was similarly unprepared for such rapid public failure. To paraphrase my song ‘Deepwater’, ‘I was in trouble and up to my neck again.’

A new manager, Alan Edwards, a shaggy-haired, charming facsimile of a vertically challenged David Essex, had spirited me away from the claustrophobia of the band’s implosion. At the time, he also managed fellow Coventrian singer Hazel O’Connor who, if I had thought about it for more than a nanosecond, was on a similar downward spiral after her success with ‘Will You’; she just didn’t know it yet.

Alan suggested that I move to London. He said that it was where the ‘movers and shakers’ lived. Long conversations ensued at his flat above a row of shops on Highgate’s main drag, about the direction of my future career. ‘Career’ – a new concept for me. Until then I had thought that radiography had been my bona fide career, while the musical success remained somewhere between a dream come true and a nightmarish hobby. I realized that I ought to be thinking more seriously about what I intended to do. Alan opened my eyes to other avenues within the entertainment industry, which was a good thing, but somewhere in our lengthy conversations, I allowed somebody else to make decisions that should have been mine. When budding musos ask for advice about how to get started in the music industry, I always tell them never allow others, particularly managers, to decide what they should do creatively. In my beleaguered experience it is a recipe for disaster.

The hoary concept of ‘networking’ had begun to find favour in London in the early ’80s. Everybody sported a Filofax bursting with names, addresses and phone numbers of people who could ‘help’ you. Mostly such people were more interested in how you could help them, but since survival in lonely London town was easier with friends, I quickly learned to network just as hard as everybody else. It was tough going. My forthright stage persona was completely contrary to my shy and reserved personality offstage. Slowly I learned to be more outgoing and fearless in everyday life, less guarded and self-deprecatory. This new strategy worked, but often I felt contrived, which made me even more defensive. I was caught in a vicious repetitive cycle, which did my mental state no good at all.

Immediately, Alan negotiated a solo deal with Chrysalis record company. In hindsight, I should have moved on to another company, but although it was not the best deal in the world, it was not the worst. The MD of the company at the time, Doug D’Arcy, was supportive and I think genuinely wanted to see me do well. I was set the task of all new solo careerists – writing a hit. The head of publishing at Chrysalis, Stuart Slater, suggested I try writing with various in-house tunesmiths, a practice that elicited some interesting partnerships. Until then my song melodies were built over guitar chords, but the songwriters I was hooked up with favoured synth keyboards. Suddenly guitars had become a thing of the past in pop music. Synths were the new cost-effective way of running a band. However, I was an old-fashioned girl, I still adored guitar played through a chorus/delay pedal and Hammond organ played through a whirling Leslie speaker.

Under company pressure, I edged further away from the ska sound that had been my public identity and closer to a marketable pop sound. The only problem was that I wasn’t writing lyrics that went with that sound. Furthermore, while in The Selecter I had created an alter ego, a feisty, angry, opinionated young woman, who had sprung from the confines of my mind like a bad Jill-in-the-box. I both loved her and loathed her. She was a means to an end; a safety net that I could fall back on when I felt that the things going on around me were getting out of my control. She was now fully fledged, eager for new experiences. Pauline Black existed and she did not want to return to the status of Pauline Vickers anytime soon.

I secretly dreaded the thought of having to go back to the anonymity of my former day job back in Walsgrave radiography department, tail between my legs, contritely obeying orders from recently promoted contemp

oraries, especially after the heady lifestyle that I had led for the past two years. Such thoughts did much to spur me on career-wise. My fame monster had been unleashed.

So, eager to please and desperate to escape seeming oblivion, I temporarily moved to London. Terry was not at all happy about the separation, but it was decided between us that if I was going to be successful in the future then I had to be where the music was made and by that time Coventry’s 2-Tone heyday was on the wane. When I left home with a couple of suitcases in the summer of 1981 I felt as vulnerable as the young girl that had left Romford to go to the polytechnic in Coventry. I was twenty-eight years old.

Terry on a weekend visit with me in London, 1982

I moved into a large room in an Edwardian terraced house in Heyford Avenue, Vauxhall. Several other people shared the house, ranging in age from late twenties to late fifties. It was an area that had been run-down, but was beginning to be bought up in large swathes by small-time property developers, intent on converting the fine old houses into rabbit-warren-like flats. The particular house I shared was a building site for much of the time that I spent there, lovingly overseen by arch-cockney ‘Mick the Brickie’, who singlehandedly knocked down walls and installed bathrooms and kitchens where previously old fire ranges and outside toilets had existed.

If I wanted to be a credible solo artist, then I had to write some new songs pronto. Alan suggested that I buy a Tascam Portastudio 144, which was the world’s first four-track recorder whose revolutionary design enabled songs to be recorded directly onto a compact audio-cassette tape. Until then recorded sound-on-sound, outside of a studio, could only be achieved with reel-to-reel tape on bulky Revox machines or their ilk. Musicians now had the ability to affordably record several instrumental and vocal parts on different tracks and later blend these parts together while transferring them to another standard two-channel stereo tape deck, which made a stereo recording that could instantly be played on ordinary tape decks. This new creative tool had even been embraced by Bruce Springsteen, no less, to record his album Nebraska, so who was I to argue!

A new Yamaha PS 20 keyboard synthesizer was also purchased with my modest recording advance. This handy though expensive piece of merchandise provided one-stop access to many synthesized sounds and drum patterns, most of which, by today’s standards, sounded artificial and sometimes downright comical. But it was portable and when headphones were inserted it allowed the player freedom to experiment without annoying other people in the immediate vicinity.

Thus began many lonely days and nights in my London bedsit trying to write new songs. And I did. The first results were considered encouraging enough for me to be hooked up after a couple of months with a writing partner, an up-and-coming young buck, Simon Climie, the future one half of successful late ’80s pop duo, Climie Fisher. At the time he had the dubious honour of being the ‘toyboy’ of former model Dee Dee Harrington, once the main squeeze of Rod Stewart. The first time I visited his flat for a writing session, Ms Harrington was very much in attendance. Probably vetting me for potential rival status.

She needn’t have worried. Simon was very talented and a really nice bloke, but with his pallid milk-fed skin, liverish lips and watery blue eyes, he was completely safe from my attentions. I stood uncomfortably in the middle of the living room watching her as she noisily bustled about in front of a mirror, combing and artfully shaking out her long blonde hair and then attaching a belt with holsters on each side containing fake guns to her snake hips, before adding chaps to her long, lean, jean-clad legs. A jauntily angled cowboy hat perched on her leonine mane completed this daring ensemble. Believe me, the effect was dazzling. I felt like a country girl who’d just arrived in the big city.

Writing songs with Simon was easy and despite our stylistic differences our output was relatively prolific. A batch of them were recorded with producer Bob Sergeant at the helm, who’d produced many of the Beat’s hits, but they failed to meet with Chrysalis’s approval.

In the meantime, Alan had suggested me for a part in a forthcoming play by a radical new black theatre company, the Black Theatre Co-operative. Inadvertently, I had gone from being at the forefront of a new British musical movement to being in the same position in an emergent black British theatre. During the ’70s, there had been an explosion of ‘alternative’ (anything that wasn’t white, straight and middle class) touring theatre companies, aiming to reach audiences outside the mainstream. Gradually the Arts Council was reluctantly forced to recognise and fund them.

Among them was Black Theatre Co-operative. It had been formed in 1979 after London fringe theatres had failed to show interest in Trinidadian playwright Mustapha Matura’s now celebrated play Welcome Home, Jacko. So he and white director Charlie Hanson had produced the play themselves. Out of this collaboration the company was born. Its remit was to encourage, commission, devise and produce new writing by black British artists and to stage popular theatre that reflected the variety of cultures existing in Britain to as wide an audience as possible. This rallying cry was a tall order given the prevailing white hegemony in British film and theatre, but the fight had to be undertaken if the artistic playing field was ever to be level. I was part of the generation of young black men and women who, driven by the inequities of opportunity, racism and second-generation higher expectations, had begun to flex their muscles in the media and, more importantly, on the street.

The 2-Tone movement and the emergence of British reggae music had heralded this new black awareness. Now the black youth had taken it to the next level. They wanted an answer as to why the police were allowed to exercise the notorious ‘sus’ laws with impunity. After the watershed riots in Bristol, London and Liverpool between 1980 and 1981, the Scarman Report was published, which laid bare the depth of indiscriminate hatred and racism within the British police force. There was a rush in the arts and media to embrace this emergent dissenting black voice. Something had to give and for once it was the Arts Council. Money, the lifeblood of all things, was made available for stories to be told about this new multicultural Britain.

The Black Theatre Co-operative benefited from this revised funding policy. A new play, Trojans, written by Farrukh Dhondy, opened the Black Theatre Co-operative’s seven-week season at the Riverside Studios in Hammersmith. Such mainstream notice was a real coup for what had been a marginalized company. I wrote the lyrics and music for the play with keyboardist Paul Lawrence, who led an excellent five-piece reggae band, featuring the superb future Big Audio Dynamite bassist, Leo Williams. The critics generally gave the thumbs down to the play. Most of them were angrily united against the playwright who, in their opinion, had sacrilegiously turned a Greek story into a black revolutionary one.

Such criticism was to be a common theme in the aftermath of the Arts Council’s largesse towards ethnic companies. Every black production was in the spotlight, which made life very difficult for potential black writers and directors and actors. The opportunity to develop a black theatre free from extreme media pressure was denied. Severe scrutiny had a tendency to stifle new ideas and led to a reinforcement of the stereotypical roles that black theatre was set up to destroy.

Fortunately, I came out of this play smelling of roses: ‘Certainly Miss Black is the best thing about this otherwise dreadful affair, her voice as expressive and appealing as ever, her backing band impeccable,’ wrote Steve Grant in the Observer.

The reviews helped me to land another part at the Tricycle Theatre on Kilburn High Road as Betty Mae, the feisty, estranged girlfriend of the near-mythical bluesman Robert Johnson in Love in Vain, written by Bob Mason. It was my first speaking part and I found myself on a vertiginous learning curve. I literally taught myself to act during the month-long rehearsals before press night on 15 April 1982. This play also contained live music, brilliantly served up by Julian Littman in the main role.

Liverpudlian actor Paul Barber (Denzil in Only Fools and Horses and ‘Horse’ in The Full Monty) played my other love interest and regula

rly ‘corpsed’ both of us almost every night, much to the chagrin of the director, but to the delight of the audience. I wore a false plait hairpiece and one night he grabbed me at the back of my neck and the plait came away in his hand. Without missing a beat he wrestled with the offending object as if it was a wild animal clawing at his face, eventually getting it under control, whereupon he threw it to the ground and theatrically stamped on it, before uttering in his inimitable Scouse tones: ‘I think it’s dead now.’ It brought the house down. Nobody could stop laughing.

Black Theatre Co-operative cast for Trojans, 1982

Again I garnered good reviews: ‘Pauline Black is particularly good as the girl from the shack next door,’ wrote Mick Brown in the Guardian. ‘Miss Black’s performance is brilliant as the frail, helpless Betty,’ commented Ital Gama Mutemeri in the Caribbean Times.

Acting seemed like such fun. It definitely beat solitary hours trying to write songs for an increasingly uninterested record company. Unfortunately, as far as I could see, but he might disagree, my manager wasn’t particularly interested in my theatrical success or my notions of a new career as an actor. For him the big money was in recording or television and film acting, not going from theatre to theatre like a travelling troubadour doing semi-political black plays. He told me that a good career offer had presented itself that I should seriously consider. Hence, by the summer of 1982 I became a presenter on a hideous children’s television quiz programme, Hold Tight, which was recorded at Alton Towers in front of a live audience. An old press release introduces the show as: ‘A new fun and games quiz with top guests for Granada TV.’

The ‘top guests’ included Toyah, the bin-bag-wearing frights that were Toto Coelo, Depeche Mode, Haysi Fantayzee, Three Courgettes (who?!) and Shakin’ Stevens. To add to the corny mayhem, comedian Frank Carson pretended to be ‘marooned on a desert island’ while teams from two schools competed to be the first to free him.

Black by Design

Black by Design