- Home

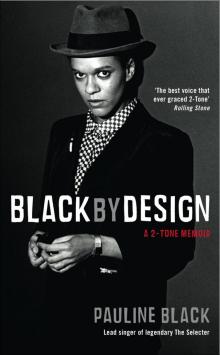

- Pauline Black

Black by Design Page 4

Black by Design Read online

Page 4

She quickly shut the door, leaving us standing on her doorstep. That was the last we ever saw of her.

My mother tried to communicate by phone and letter, but all to no avail. Not to be deterred, she travelled all the way to the eel and pie shop in Bow where she knew that Mrs Sparks did some part-time work. On arrival there was no sign of her. My mother discreetly asked the skinny young woman serving behind the counter whether she knew what had happened to her. The shop was empty after the lunchtime rush, so the woman was well inclined to chat.

It transpired that Mrs Sparks had left her job some weeks ago, but the woman had heard on the grapevine that her daughter Janet was six months pregnant by an unemployed West Indian drug dealer and now lived in a squat in Ladbroke Grove. Warming to her theme, the woman said that the Sparkses had warned their errant daughter that if she came home with a black man, they wouldn’t open the door to her. Since Janet had refused to visit them without her boyfriend, they cut her off completely. How cruel, I thought. How could they ever have really loved her?

During my teenage years, Janet was held up as an example of a ‘girl gone bad’ because she had been ungrateful and gone the way of the ‘dirty girls’. This mantra was dinned into me for so long and so hard that I was completely paralyzed in the presence of black men for some number of years after I left home, as bizarre as that sounds. It was as if both our adoptive mothers fervently wished to breed the black out of us. By then there was a generation of these kinds of well-meaning women doing just that to a new generation of ‘coloured’ children. I don’t know what happened to Janet Sparks and her baby. I wish I did.

So, why did my mother choose a black child if she had so much antipathy towards black people? Didn’t it occur to her that my ‘colour’ was going to be a future issue, which couldn’t be swept under the carpet and ignored? The initial decision to adopt a child into the family had been made after my mother developed a facial paralysis known as Bell’s Palsy, which had rendered the left side of her face like the molten wax drips on a candle that has been left in a draught. The viral infection of her facial nerve destroyed not only her looks but her confidence too. She was reluctant to go out in public in case people stared or poked fun at her. Her health began to deteriorate as she became more reclusive.

Our family GP, a rotund and florid whisky-drinking Scotsman, Dr Donald, decided, in his wisdom, that what she needed was something to take her mind off her appearance. How about a new baby? Babies were considered a common panacea for all womanly ills in the ’50s. Unfortunately, my mother had had a hysterectomy after the birth of Roger, so technically another child was impossible. So Dr Donald helpfully suggested an adoption.

In those days, prospective adoptive parents were invited to view a row of available babies and then asked to choose one. That is so scary. As a child, I often wondered what would have happened if I hadn’t been chosen, or indeed, if I had been picked by somebody else. Presumably people just walked up to a crib and said: ‘Ooh, that one looks nice, we’ll have that one, please.’

Fortunately for me, the other children available for adoption on the day that I was chosen were boys. After rearing four boys already, my parents desperately wanted a girl. So much so that they didn’t care what colour it came in. This child supermarket, where I was on ‘special offer’, was called Sunnedon House in Coggeshall near Braintree in Essex. Coggeshall is a picturesque, sleepy little village, full of quaint clapboard houses, whose garden gates whisper to each other of gentler times; a perfect place to hide the disgraced pregnant young women who came there to give birth.

I’ve since discovered that back then the countryside was awash with ‘Mother and Baby Homes’, most of them run by the church. Such Christian do-gooders thought that depriving a bastard child of its identity would be beneficial in the long term, even more so if it was a ‘coloured bastard’. The mother’s shame was hidden and the child relocated to other benevolent families or orphanages – problem solved – a win-win situation for all those involved. The sweet smell of charity perfumed the rank stench of hypocrisy that underpinned such Establishment philanthropy.

Similar hypocrisy is still evident today, exercised most notably in Africa. I am physically sickened every time I listen to some vacuous pop star or actor prattling on about ‘how they didn’t realize things were so bad in Africa’ after a visit to a new war zone’s refugee camp. Often their solution to the beleaguered continent’s problems is: adopt a black baby. Imbeciles! They completely miss the point that the reason why things are so bad is the legacy of colonialism and the intransigence of the International Monetary Fund. These twin evils make the nations beggars and their people paupers. You cannot draw lines on a map and make up the names of nations comprised of differing tribes. Suddenly these people are thrown together and are forced to compete for resources. The black people left in charge after the colonialists decamped to Blighty had been educated to be just like their departing white overlords, so how can any of us be surprised at the messy inheritance that remains in most African countries.

The periodic violent coups and deathly famines that beset the continent are seen by the developed world as evidence that black people are incapable of governing themselves. Well-fed celebrities flock around famine victims like brightly feathered vultures. They alight from helicopters and 4x4s to bask in the flashing cameras of half the world’s press, eagerly maximizing their photo-ops amid the devastation so they can show the world how much they care. Sometimes they pluck some poor unfortunate child from the clutches of starvation and spirit them off to a life of plenty in palatial surroundings, never once thinking about the future consequences of their actions for the child. Most often, we mere mortals are tearfully exhorted to give, give, give while the IMF quietly takes, takes, takes. Enough. Saint Bob Geldof and Madonna eagerly campaigned in recent years to ‘Make Poverty History’, but surely the real aim should be to ‘Make Wealth History’. Bet they wouldn’t be so keen on that.

In the meantime, back to the ‘buy one get one free’ offer at the kiddies’ supermarket. I do not wish to sound bitter about the good fortune of my adoption. I am grateful, to whom I don’t know, but I am very grateful that I was chosen and taken home, however it happened. At that time, the alternative would have been an orphanage, probably the Dr Barnardo’s Home in Dagenham. I’ve since met a few of the inmates who were in a similar position to me, and they are all damaged in their own ways, not from the Home per se, but from growing up in an institution as opposed to a loving home.

At first, my new parents fostered me with a ‘view to adoption’. That phrase always made me laugh, whenever my mum said it. Fostering sounded like a first-floor window with a bright adoption vista on the horizon. The envelope that had been so meticulously written on by my real mother was registered, because it was used to send money to my mother for my upkeep each month. I was told that eventually the money dried up, so I was legally adopted at eighteen months old. I often wondered what happened in the intervening period. Did my mother visit me? The copy of Treasure Island that I had discovered suggests that she did. Did I pine for her? I would never know.

Me at eight months

I cannot say that I wasn’t loved. I know I was. But I grew up feeling like a cuckoo in somebody else’s nest. It’s bad enough not looking like anybody in your family, but it is very confusing not being the same colour as them. Somehow it was like being doomed to play catch-up for the rest of your life. Nobody in the family had the language to deal with it. Nowadays, families are given instruction by social services about how to deal with the problems that might be thrown up by adopting mixed-race children, but no such checks and balances were in operation then. It was a case of ‘suck it and see’. Unfortunately, my family didn’t consider it a problem. Well, it wasn’t for them.

When Mum told me that I was adopted, she had said that adopted people were ‘special’. I have never figured out exactly what is special about being adopted. In common parlance, ‘special’ is used to describe a ‘one of a k

ind’ or something that is admired, precious or irreplaceable, but in reality it usually denotes something that is not acceptable, good or wanted, hence ‘Special Olympics’, ‘Special Needs’, where the word is used to denote a deficiency. Is it a deficiency to have too much melanin pigment?

Throughout my early childhood I longed to be special, just like my mother had promised; that was the biggest white lie of all, because I soon learnt that it is possible to be ‘special’ for all the wrong reasons.

TWO

‘I’LL HAVE SOME OF THAT’

My dad, me and my mum

It began at age nine and it stopped in the summer of the same year that I passed my 11+ exam and changed school.

Opposite our house was a road full of small, well-kept front gardens and neat houses, a pleasant short cut that led to a subway under a busy dual carriageway. In 1962 a troll moved into the last but one house at the far end of the road. His name was George. His first wife had died and he had recently re-married. The new wife, Doris, was a good few years younger than he was.

George was a friend of Ken, my second oldest brother who, by now, worked in a furniture shop in Romford called Killwicks. George got him the job. Ken was a born salesman and since the newly introduced hire purchase had proved so popular with housewives, he made a good living. People loved Kenny, as he was affectionately known. He had an open face and a winning smile and could charm the birds from the trees when it came to selling something to somebody, whether they wanted it or not. What few people knew was that he was adopted too. However, he was white and about fourteen years older than me. I looked on him as a kind of role model after I found out about my own adoption. He seemed to have taken his lack of real parentage in his stride, so why shouldn’t I?

George was also a friend of the family of Ken’s wife, June. They were a typical cockney family from Dagenham. They would have family get-togethers, which seemed to involve their entire street descending on their house to smoke copious quantities of cigarettes and do some serious drinking. I hated their parties. My eyes would smart from the acrid smoke in the room. The adults wore colourful paper hats and after enough booze would start raucously singing music hall songs like ‘Roll Out the Barrel’ and ‘If You Were the Only Girl in the World’ at the tops of their voices, while I handed round plates of spam sandwiches and bowls of homemade pickled onions.

George would sit holding court on the sofa with a big smile on his face, chomping a cigar and being the life and soul of the party. When he saw me approaching with the sandwich platter he would wink at me and always say: ‘I’ll have some of that.’

It was his favourite catchphrase. People loved to hear him say it and some of them tried to copy him, but never with George’s sense of comedic timing.

Me aged nine

Everybody loved George, except Mum, who used to refer to him as looking like ‘old Christie’. She meant that he resembled John Christie, the serial killer of 10 Rillington Place fame, who was hanged for his crimes a few months before my birth. And he did.

He had a large, domed head, with a few dark strands greasily trained across the leprous expanse of skin covering his bony skull. Thick horn-rimmed spectacles completed the similarity to Christie, magnifying his steely gaze. He revelled in the notoriety that this resemblance gave him and delighted in telling anybody who would listen of how once a young woman ran out of the compartment on the Romford to Liverpool Street train when he got in the carriage, shouting: ‘It’s him, it’s him. It’s Christie.’

He would laugh when he told the story and he related it often. Even his friends told the story for him in his absence, if his name came up in conversation.

How it began, I don’t know. All I know is that it did. I visited his comfortable house with its white, decorative shutters, situated on a corner plot overlooking the main Romford to London arterial road, every Sunday afternoon at his wife Doris’s request, ostensibly to help out with their young child. This arrangement had been sorted out unbeknown to me, but probably Ken was used as a go-between.

The house had a long front garden and a small wall in front. It was semi-detached and had three bedrooms, as well as an upstairs bathroom, which I considered a luxury, because at that time our toilet was still outside. There was a spotless fitted kitchen just off the living room at the back and a sitting room at the front. Guests were entertained in the sitting room. It had a big TV with a wood surround, a three-piece suite in the deco style and a huge, carved dark mahogany sideboard that gave the room a funereal air. It was a big room, bigger than the rooms at our house, but maybe I just remember it as big because of the enormity of what happened there.

I liked to help his wife Doris with her year-old baby boy. I was never entrusted with the child, being considered too young then, but I was allowed to make myself useful, buttering bread for sandwiches and laying the table for tea, while she played with Junior. I had an ulterior motive in keeping myself busy at all times, because while I was doing useful chores, he couldn’t touch me. I rarely stayed safe for long. Eventually he would think up some pretext for spiriting me away from Doris and I would find myself at his mercy again. He never worried about discovery.

Sometimes Doris would be out when I arrived, but he would always tell my mother, who usually delivered me to the house, that she was expected back shortly. These were the times I feared most. I wanted to scream at my mother not to leave me, but I never did. George assured her that they would drop me back home at 7 p.m. That gave him four hours to do things to me that I knew were wrong, but I didn’t have the vocabulary to be able to explain what was happening.

I wasn’t raped. I am eternally grateful for that. He enjoyed kissing and touching. I was nine and he was in his forties. Whenever an opportunity arose to indulge his passion, he attached himself to me like a leech and somehow he couldn’t let go. Something would have to happen, like the creak of a door, a doorbell ring or a baby’s cry before he felt impelled to stop what he was doing. The sorry business was executed silently.

I still cannot imagine why Doris didn’t think that something was not quite right about her husband. His favourite trick was to insist that I help him put the baby to bed just before I went home. Doris was usually busy in the kitchen washing up, so she thought he was just being a helpful hubby. She lavished praise on him for his thoughtfulness.

As soon as Junior fell asleep, he would molest me next to the crib. In hindsight, such behaviour seems unbelievable, but I didn’t know how to go downstairs and start a conversation with his wife, which would begin: ‘By the way, do you know that your husband…’ Instinctively I knew she would not believe me. Probably nobody else would either.

When I hear the stories of other abuse sufferers I am always staggered by the everyday nature of the crime. It is not that you are captured in the street and dragged off into the undergrowth and raped, that would be bearable almost, because you could prove to everybody that a crime had been committed, but when an adult man French kisses and intimately touches a child, that is not something that leaves any tangible evidence. It is not something that a child can put a name to. That is the tragedy. The only evidence is the invisible mental scar. That is the crime.

When I finally got round to telling my parents, all hell broke loose. It had been a typical Sunday. I had walked to the house on my own, because I was nearly eleven now and I didn’t need my mother to take me. Doris was not in when I knocked, only George. I knew what it would mean as soon as I set foot in the house. He would be on me. His hands would be on me, his mouth would be on me and I would submit, mainly because I didn’t know what else I was supposed to do. I resigned myself to my fate.

He seemed to be wherever I went. He was always present at parties, wedding receptions and christenings that we went to; he would turn up to sports day with my brother Ken at Romford stadium, probably to ogle the girls in their gym knickers when we ran in the schools championships. Once he had mentioned that I shouldn’t tell anybody about what he was doing because they wouldn’t un

derstand. I never thought to question why they wouldn’t understand. His adult status lent him an authority that was beyond questioning by a mere child.

Parklands Junior School relay team at County Championships, Romford stadium, winning the 440 yards relay, me far left, aged ten

His behaviour didn’t arouse suspicion in others. He held down a good job; children came to play in his house; he had a small baby and another one on the way; he drove a good car. He was normal, therefore I tried to tell myself that what was happening must be normal. While I was in the house, I was the centre of attention. I was special. But I didn’t want to be that special. I just wanted it to stop.

Sometimes I would think that it had stopped. I was allowed to spend a couple of hours unmolested, but eventually I would be manoeuvred into a place where he could grab just a few minutes with his hands on me.

On the fateful day that I finally spilled the beans, he had plenty of time to do whatever he wished, but unfortunately unlimited access to the sweet shop made him sick. He laid me down on the floor and got astride me. Suddenly things went too far, this was more than just touching. He was pushing something hard against my leg and making grunting noises. Then the doorbell rang. He jumped off me like a scalded cat and ran to the bay window. I heard him say: ‘Shit, it’s Doris. What’s she doing here?’

As he hurriedly turned away from the window, I noticed that the front of his trousers was undone, revealing a fleeting glimpse of something pink and fleshy. What I saw frightened me. He must have seen where I was looking and hastily rearranged himself, using the moment to bark: ‘Get up off the floor and pull your dress down.’

Black by Design

Black by Design