- Home

- Pauline Black

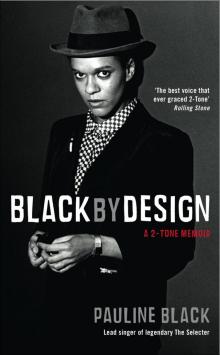

Black by Design Page 7

Black by Design Read online

Page 7

As soon as the song finished I wanted to know more about this woman. Instinctively I knew she was saying something profound that would affect me for the rest of my life. By the time I got to see her filmed performance of the song on Top Of The Pops, I was a fully paid-up devotee. The sight of this proud black woman, with her unprocessed hair in a natural Afro, walking down the street like a modern-day African Queen, singing such a simple powerful truth, made my heart swell with pride – this new black pride that was increasingly being talked about. Recently, slogans like ‘black consciousness’ and ‘black is beautiful’ regularly appeared in the media. I had reached the age where I needed to hear that from somebody.

I had begun to buy make-up like all the other girls at school, but brown foundation creams had yet to be invented at British beauty counters, which were awash with chalky, rose-tinted concoctions designed to aggravate teenage spots and acne. My mother’s response to how I looked after a lengthy session applying it said it all: ‘You look as though you’ve dipped your face in a flour bin.’

Even buying a pair of tights was fraught with danger. My legs, encased in the unflattering burnt umber hues of ‘American Tan’, looked as though they belonged to some other person. It was as if black people didn’t exist on the high street and, in terms of spending power, they didn’t.

Until then it had never occurred to me that how I wore my hair was a political decision. Articles began appearing in newspapers and magazines, not many but enough, talking about the new Afro hairstyle being worn by black women in America. No more ‘processed hair’, trumpeted the headlines. I didn’t even know what ‘processed hair’ was. I thought it was some kind of wig. Hot combs, relaxers and the concept of ‘conking’ were unknown to me. I naively – and in retrospect, laughably – thought that Diana Ross’s impossibly high, elaborately tonged, glossy, straight black hair was real!

Also, the word ‘black’ had begun to be used; not negro or coloured, but telling it like it is, black. And not just the word black, but Black with a capital B. I loved this new word and began referring to myself as Black at every available opportunity, much to the consternation of my mother, who argued: ‘You are not black. Don’t keep saying that. You are coloured!’

Such a response was like a red rag to a bull. By 1968 war was declared in the house. My raison d’être was to defend ‘blackness’ no matter the cost to familial relations.

The year began with Louis Armstrong releasing, or rather unleashing, the song ‘What a Wonderful World’ on the British public on New Year’s Day. It instantly went to No. 1, even though everything in the world was decidedly not wonderful. It’s interesting that it was also released in the USA where it bombed dismally. The contradiction between the reality of the American homeland and the song’s fantasy universe was too stark to fool the public.

I hated the song. I consigned Louis Armstrong – in retrospect totally unfairly – to ‘Uncle Tom’ Siberia. I loathed it that white people loved the way he sang the trite lyrics. He was the acceptable face of ‘coloured’ and I was having none of it.

‘Oh, he sings that lovely,’ my mother opined every time it came on the radio. ‘Such a shame he sweats so much.’ Why Louis Armstrong’s sweating habits should matter is something that only my mother would be able to explain.

Ironically, ‘What a Wonderful World’ kicked off the year that informed my thinking for the rest of my life. It was the year when everybody got to see the mess that was happening. It was the year that the revolutionary funkster James Brown would name a people, not just in his country, but worldwide, with the famous slogan ‘Say It Loud, I’m Black and I’m Proud’. It was the year that two black athletes, Tommie Smith and John Carlos, raised black-gloved fists at the Mexico City Summer Olympics and symbolized the dissatisfaction of a people for ever. It was the year that the magical whirling dervish Jimi Hendrix recorded ‘Voodoo Chile’ with the opening lyric of ‘Stand up next to a mountain, chop it down with the back of my hand’ – the best lyrical indictment against racism coupled with a call to arms that I have ever heard. The sense of empowerment for blacks was palpable.

And yet that same summer, Dr Martin Luther King was gunned down by a single bullet on the Lorraine Motel balcony in Memphis in April and a few months after, Robert Kennedy, the Democratic presidential nominee, was gunned down in a dirty kitchen passageway at the Ambassador Hotel, Los Angeles, after delivering a victory speech in the wake of winning the Californian primary.

So much for civil rights legislation! It was ‘open season’, not just on blacks but on white liberals too. I watched in awe as the world unravelled. Suddenly young people, particularly students, were on the march. American blacks were rioting in most major cities; all seemingly wanted their pound of white flesh as indignity was piled on indignity until only burning hatred prevailed. The world was crumbling and yet in Romford nobody seemed to notice. I had to get out of there.

But what could I do? How could I make any kind of definitive statement from such suburban solitude? Then I hit upon an idea. It was late October 1968 and the newspapers were eagerly promoting a new musical that had just hit Britain, Hair.

Hair was Broadway’s groundbreaking rock musical. The Vietnam war was escalating, so Hair’s plot about a New York street kid and his friends deciding if he should burn his draft card was very topical indeed. The original London cast even included such present-day theatre stalwarts as Tim Curry, Paul Nicholas and Elaine Paige. The songs about sex, drugs, race and personal liberation were controversial, and the musical caught the Zeitgeist of the time. The biggest stir happened at the moment before the interval when the entire cast appeared naked under a dim blue light. How typical that England should be more preoccupied with the concept of nudity than with the concerns of humanity.

Even more ironic was the fact that the cast member who garnered most publicity – even though she had only two lines of dialogue – was a nineteen-year-old American, Marsha Hunt. This Afro-haired piece of gorgeousness became the first black woman to appear on an up-market magazine, Queen. She dated Mick Jagger, signed to Track records (also Jimi Hendrix’s record company), and appeared on Top of the Pops, singing a hit single, all within a matter of months.

I was knocked out. She was indeed the ‘sweet black angel’ that Jagger would sing about on ‘Exile on Main Street’, and her achievement offered a much-needed way forward for me. If she could succeed with her chosen goal, despite being labelled black in a white society, then so could I. She looked wild in her fringed buckskin outfits and hippie-ish ensembles, completely at odds with the manufactured, manicured sophistication of Diana Ross. Her innate originality made me want to be her, but since this was impossible, I settled for the next best thing: I wanted her hair!

My hair, or perhaps I should say the lack of it, became a singular preoccupation. I normally regarded it as an inconvenience on top of my head, something that was rarely remarked upon with any civility, constantly described as frizzy or woolly and apparently longing to have white hands reach out and touch it at every opportunity. That was the main trouble: in those days white folks just loved to touch your hair or your skin. They always expressed surprise after a casual feel, usually saying: ‘Ooh, I thought your skin would be leathery,’ or another favourite, ‘Ooh, your hair’s really soft, well, I never.’

Such treatment had led me to be very mistrustful of people and their prying hands. Prior to Ms Hunt arriving on the scene, I yearned to have the poker-straight, shoulder-length tresses of my white girlfriends either with a heavy fringe or parted in the middle. Such hairstyles were the epitome of the ’60s ‘cool’ generation. Therefore a curly mop of hair on top of my head, in a fashion world ruled by Marianne Faithfull, Twiggy, Jean Shrimpton and Penelope Tree, seemed like God’s cruel joke for an over-sensitive teenager.

The role models that existed had hair creations that seemed to defy gravity, humidity and credibility. I studied photos of the girl groups on the Motown label or some of the ladies that graced the Stax label for some

kind of clue as to how they successfully managed to coax their hair into the semblance of a Mr Whippy ice-cream cone, but I’d never heard of straightening combs or flat irons, the gothic horror tools that got the job done. I didn’t know that ‘black hairdressers’ existed. My mother cut my hair and didn’t have the faintest idea how to do it. Her idea of styling was dangerously close to trimming an unruly hedge.

I had found my perfect role model in the wilful goddess, Ms Marsha Hunt. Little did I know at fifteen that in eleven years’ time we would meet under wholly different circumstances in Los Angeles, with me as the pop star and her as a working single mother.

But, for now, here was somebody who had a head of hair that I could aspire to. Marsha Hunt was hard not to notice. She cropped up everywhere in the papers, magazines and television. I followed her progress with interest, and a huge amount of glee. I cut out any photo of her that I could find and pinned it on my wall.

My new fascination didn’t escape the notice of my mother, who made it quite clear that she did not approve of my new heroine. My mother’s ideas of suitable black females to emulate were Winifred Atwell, a rotund, jolly black Caribbean piano player on the odious Billy Cotton Band Show, or, diva of all divas, Shirley Bassey. Much to my mother’s horror, I nicknamed Ms Bassey ‘Burly Chassis’. I loathed her stentorian singing style, her revealing sequined gowns and her cheesy perma-grin. She was not the role model I craved even if she was homegrown talent and came from Tiger Bay in Cardiff. As far as I was concerned, both of these women belonged to another age, an age of ‘knowing your place’. Marsha Hunt represented the ‘shock of the new’. Black people were on the rise.

In order to incense my mother further, I painted ‘Say It Loud, I’m Black and I’m Proud’ on a large piece of cardboard in black paint, with a clumsily designed clenched black fist beside it. This huge statement now hung on my bedroom wall, directly opposite the door she entered every morning to give me my wake-up call. She would mutter under her breath, ‘This sort of thing is turning your mind,’ and ‘No good will come of it, you know.’

‘How wrong can you be,’ I thought, pretending to be asleep. ‘You’ll see.’

In 1969 I became aware of the Black Panther Party in America who were championing a radical new concept, ‘Black Power’. Everything about the Panthers was provocative: their Maoist-inspired political slogans, their ubiquitous black berets and leather jackets, their clenched-fist Black Power salute, their big Afro hairstyles, their practice of openly bearing firearms, and their disciplined militancy and revolutionary political vision. The Black Panthers not only fired the imagination of their generation but also shifted the strategy of the African-American struggle and all movements for justice and social change in the United States by seeking solutions rooted in a basic redistribution of power.

That’s all I needed to know. My imagination was captured, even though it was more hook, line and blinkered, rather than sinker. I would be an English outpost. As the only raw recruit in Romford, I needed to get a black beret from somewhere and a big Afro, not necessarily in that order and never mind that trying to fit an Afro under a beret defeated the object of the Afro in the first place.

Obtaining a black beret was the first hurdle. I decided to eschew pocket money expense and settle for my school beret, which was actually navy blue, but the next best thing to black given my meagre resources. I hid the school badge by wearing it back to front.

I began to grow my hair from the tiny patted-down-with-water growth of curls that it was, into a full-bodied, proud Afro. Anyone who has ever tried to grow an Afro quickly soon realizes that this can take a few months. During this interminable growth period I sat and passed eleven GCE ‘O’ levels. I was pleased that my after-school revision stints in the library had paid off, but I could have done with a bit of help during the next step, deciding what to study at ‘A’ level. My parents didn’t really know what I had achieved, but just that the number of subjects seemed a lot. I recently read that a distinguished Harvard economist, Martin Fryer, asserted that mixed-race adolescents ‘– not having a natural peer group – need to engage in risky behaviour to be accepted’. I’m not sure if he is generally correct or what he bases his evidence on, but in my case he was spot on. At this point in my life I opted for the riskiest behaviour possible: I chose to study biology, chemistry and physics at ‘A’ Level, instead of English literature, French and history, in which I had got top grades. Perhaps I felt I needed the challenge? I don’t know, but I sometimes wonder how my life would have turned out had I not gone down the road less travelled. Maybe it was just a cunning plan to have a class full of boys at my disposal without any female competition gumming up the works. Who knows?

At the beginning of the new sixth-form term, I was ready to embark on my first covert black guerrilla mission at Romford Technical High. This took the form of a meticulously planned assault on my ‘A’ level physics class. I got up early that morning and prepared my hair by ‘freaking’ the whole thing out with the aid of an Afro comb, a newly acquired piece of kit sourced in the local Woolworths for my covert arsenal. No holes or bits of fluff were allowed in a perfect Afro. The illusion of a faultless sphere was paramount. Easier said than done, it usually took half an hour of painstaking teasing to get the desired effect. I stared at my reflection in the mirror when I had finished, completely awestruck. For the first time in my young life, I thought I looked that indefinable thing – cool.

I smugly went downstairs to the kitchen to eat my breakfast, but even before I sat down at the table, my mother took one look at me and screamed: ‘You look like a bloody golliwog. Go upstairs and pat it down with some water right now. You needn’t think you’re walking down the road looking like that and making a show of yourself to the neighbours.’

‘No!’ I shouted back as I grabbed my satchel and flew out the door.

That ‘no’ was my entry into adulthood. Of all the words that she could have used, she used the word ‘golliwog’, malevolent little beasties still much prized in some Nazi circles today. Even though I had unknowingly cherished a golliwog that Aunt Rose had seen fit to give me for my first birthday, it had been consigned to the bin when I became conversant with the political notion of black racial pride. Now I hated the little fuckers in their stripy pants and blue jackets, with their red-lipped grins – racist icons perniciously masquerading as children’s cuddly toys. My library research had even revealed that golliwogs had female counterparts, pollywogs. Not a lot of people know that.

My Afro was huge. Look at me, the Afro screamed, as it bobbed along on my head, oblivious to the stares of passers-by; it was as if it had a life of its own. It was wearing me, not the other way around. It bounced contentedly while surveying the world from a lofty height and, by comparison with its very hipness, everything else looked outdated, outmoded and, dare I say it, plain lame.

My first class that morning was physics. I hoped there would be many of the same stupid boys in attendance who had jeered at me behind the teacher’s back during a practical class about thermodynamic law in my ‘O’ level year. ‘Hot stuff’, the ringleader of the most troublesome group had shout-whispered at me while simulating masturbation. I had wanted to scream back at them, ‘Black body radiation,’ ha bloody ha, ‘so black bodies absorb heat and light, big deal, get over it.’ But I couldn’t.

I wasn’t sure if it was the implied sexual connotation that upset me so much or just the mere fact that white bodies reflecting heat and light sounded much more ideal. Call me over-sensitive but, believe me, simple little things like this reinforce that hoary old homily that black is bad and white is good. So fucking stupid, but so fucking all-pervasive. It was difficult to cope with such boyish nonsense. I had already discovered that answering back usually led to more embarrassment rather than less, but not answering back left me vulnerable and easy prey; I hated that.

This was the first day with a new physics teacher, a recent postgrad, who had only started at our school the previous term. He was not onl

y comparatively young, but also quite hip, meaning that he wore jazzily patterned ties and cool specs. I hoped he would be more on the ball when it came to maintaining discipline than the profoundly deaf and arthritic former physics master that he had replaced.

Our new sixth-form status meant that we had graduated from the classroom to a lecture theatre situated in a purpose-built science block on the other side of the road opposite the main school. The lecture theatre had serried ranks of desks rising upwards from the floor. Their stacked splendour looked very grown-up, reinforcing the fact that we had lectures now and not lessons. The room had no natural light, only the sickly glow of fluorescent strips in the ceiling, which made white flesh look particularly leprous and fish-like. The ventilation was scant too, emphasizing the fact that boys paid little attention to their body odour.

When I marched into the room sporting my new hairdo, the entire class shut up, simultaneously relaxed their lower jaws, and stared at me like dead fish. I stared right back, or perhaps I should say my new hair creation defiantly stared back. Even the teacher raised his eyebrows. I sat down in the middle of the third row – the first three rows were always left vacant – and just stared ahead. I thought I would give them the best view of the ‘do’. Twenty pairs of eyes bored into my back. Result: ‘That made you sit up and notice,’ I silently murmured to myself. ‘One small Afro for Pauline, one giant poke-in-the-eye for schoolboykind.’

I’m not sure what I was trying to achieve by this simple defiant act. Perhaps it was just a cry to be noticed, or perhaps everybody, despite their circumstances or colour, has to define their youthful self with a flash of self-identity. But it must have worked because nobody took the piss out of me again. For once I had pushed the agenda. I was no longer in thrall to the poker-straight, lemon-haired brigade who swung their long tresses between their bony shoulder blades as they walked along the road for every building worker to whistle at. My Afro was at war with their Englishness and I loved every minute of it.

Black by Design

Black by Design